CASE STUDY: Kenya and the 2015/2016 El Niño - ENSO amplification and forecasting failures

Comparing CHIRPS rainfall and anomalies in ENSO and IOD strength for 3 strong El Nino events

Intensification of the hydrological cycle is a key impact of climate change, exemplified by past and continuing amplification of ENSO cycles as a result of global warming, spanning all CMIP models. Cause for this amplification is debated, with some suggesting anomalous surface winds alter Southern Ocean heat uptake patterns, while others link it to increased sea-surface temperature at the tropics, driving stronger rainfall. While the cause may be debated, the impact is not, with increasing ENSO strength having been linked to severe regional droughts and flooding worldwide.

The El Niño event of 2015/2016 was one of the most severe on record, leading to predictions of extreme flood events in Kenya. There was strong precedent for this, as the similarly strong El Niño event of 1997/1998 had devastating impacts. It resulted in 10 months of extreme heavy rainfall, with landslides, floods, proliferation of diseases, destructions of homes and livestock, and losses of thousands of lives.

Comparing cumulative precipitation and WASP values in Kenya for strong El Nino years

However, in defiance of most national and global meteorological institutions, Nairobi saw near normal rainfall in the 2015/2016 wet season. While 1997’s peak event had a return period of 15 years, 2015 peak flows only had a 1.5-year return period, meaning less widespread and long-lasting disruption. The surprisingly low precipitation during this period has been widely attributed to a weakness in the Indian Oceandipole, which was strong during the 1997 El Niño.

While widespread flooding was limited, impacts were severely felt in some regions, especially those coastal or near the banks of Lake Victoria. Fortnam describes flood damage in Vanga, a rural coastal town, with many homes destroyed, trade severely disrupted and an increase in waterborne disease; mostly attributed to poor infrastructure. Subsistence farmers strongly felt the effects of flooding, with delayed harvests during planting season, a time when food stores run low, exacerbating food insecurity. As Kenya has little temporal buffer between rainfall and flood onset, vigilant forecasting and mitigation is paramount. Combined with strong institutional memory of extreme flooding, the nation was overprepared for disruptions, leading to experts being concerned about officials ignoring forecasts in the future.

“in 1997 everybody was a victim”

“it just had impacts in particular zones”

Quotes from key meteorological and management officials

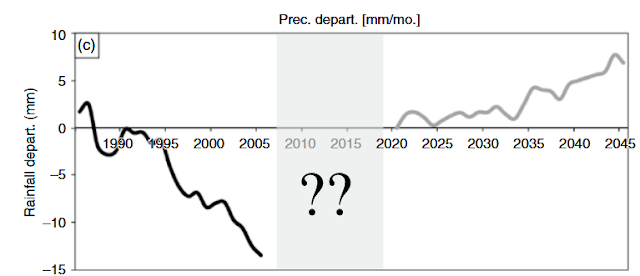

This case study illustrates that a core danger brought about by anthropogenic climate change is the increasing unpredictability of weather events, partially resulting from the uncoupling of previously concurrent climate phenomena (i.e. ENSO and IOD cycles). Forecasts are central to many mitigation and adaptation strategies, but rely on accurate understanding and modelling ability – which is complicated by failures such as the East African Climate Paradox in most projections.

Observed rainfall anomaly vs CMIP5 predicted future anomalies for East Africa

Hi Arushi. Enjoying your blog so far.

ReplyDeleteYou talk about the flooding impacts at Vanga. What exactly about the infrastructure was poor? What preventative measures could've been put into place? The paper linked suggests that there are small holder farmers on the bank growing rice, a crop that is somewhat reliant on being on a flood plain. Could creating infrastructure to prevent flooding cause social issues within the community by reducing crop production?

Look forward to seeing your response!

Tim

Hi Tim,

DeleteThanks for the comment! Vanga's rural status means hard flood mitigations or aren't present for the River Umba in the same way they are for other catchment tributaries. They've also had some significant degradation of their mangrove forests, and a lot of the region live in mud and thatch homes, which are uniquely vulnerable to flooding.

I think the conflicting needs of farming and flood mitigation is a really interesting topic to explore. Risk-based flood management is a popular option for flood-prone areas in South East Asia, but is not consistently effective. Seeing as these are mostly small-hold subsistence farmers, there could be much more catastrophic consequences for people's livelihoods and food. Infrastructural considerations are usually top-down, and have also historically struggled with considering rural and subsistence farmer voices, so there is no guarantee that these conversations are happening at a government level.

Aarushi